''Peer reproduction''?

Key signing parties between trust and subtle othering

Silke Meyer (Freie Universität Berlin)

"Peer reproduction?" Key signing parties between trust and

subtle othering by Silke Meyer is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Germany License.

A short introduction to key signing parties

Key signing parties are a ritual belonging to encrypted electronic

communication. They take part during congresses or big meetings of the

free software community.

I will shortly summarize what happens at such a party:

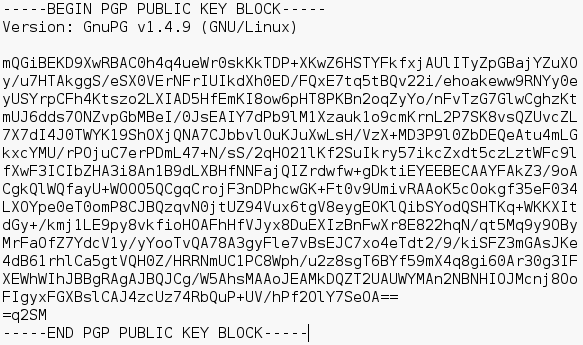

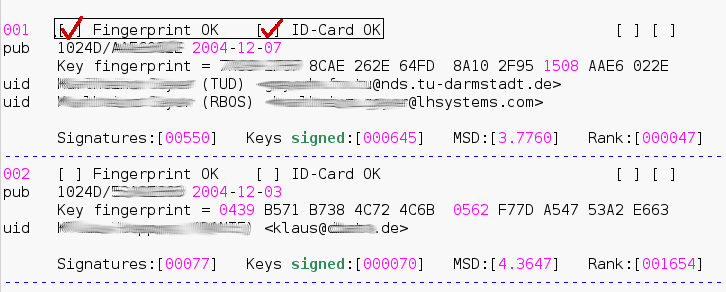

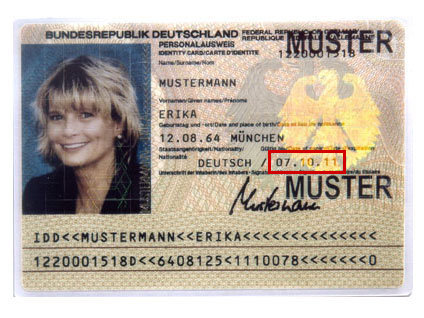

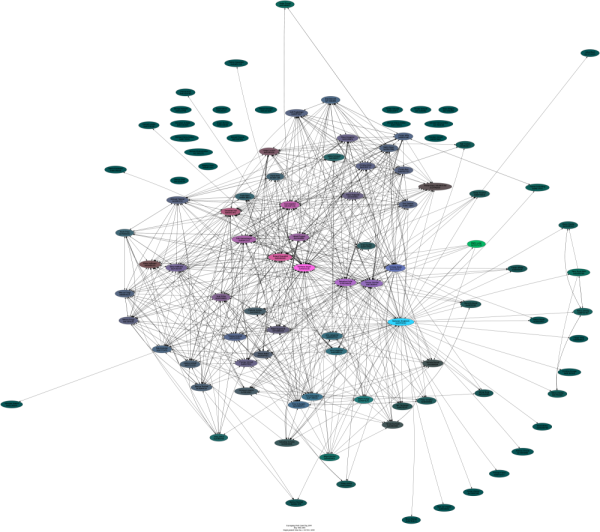

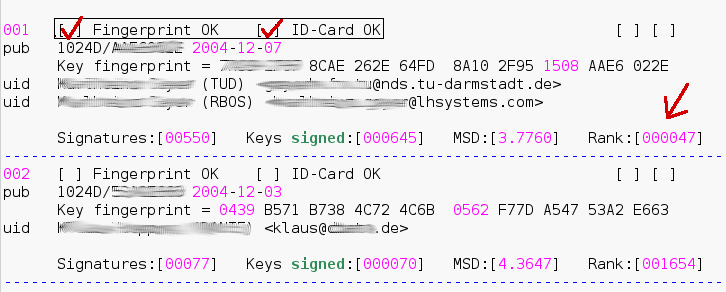

Figure 1: A gpg key in text form

People generate a pair of keys (a public and a private key). They

publish their public keys on the internet or send them to communication

partners via e-mail. The public key is used by others to encrypt an

e-mail to the owner of the key. Only this particular person should be

able to decrypt the message.

Key signing parties are arranged to assure that public keys really

belong to the person that allegedly published it. The authenticity of a

key is certified by the digital signatures of those who have checked the

“true” identity of the owner.

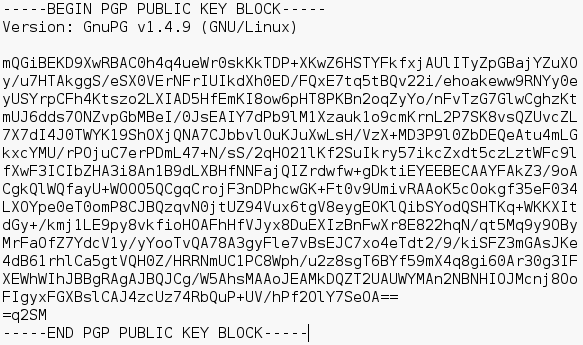

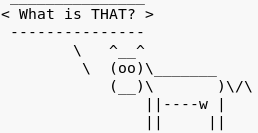

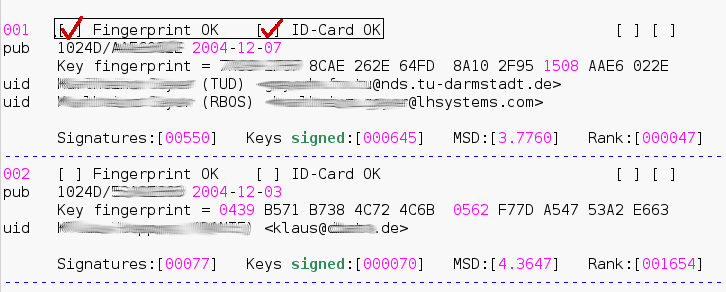

Figure 2: Signatures on a gpg key are publicly accessible on the

internet

The idea behind this is that not everyone is able to check every

identity because people live too far away from each other. But if one

can rely on signatures which others have given to a key, one can assume

that a key is authentic. This notion is called “web of trust”:

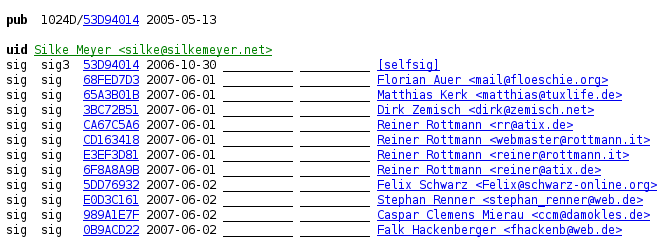

Figure 3: The "web of trust" between the participants after a key

signing party

(published on

http://wiki.linuxtag.org/w/Keysigning_2008 by the organizer)

A has signed keys with B and C, so B and C could “trust” each other's

keys, because there is a linkage, namely A's digital signature on both

their keys. Big key signing parties with many participants make this

''web of trust'' grow very fast. One could say that the ''web of trust''

is a network of individuals who want to be sure about the 'true

identity' of their communication partners.

Observations

It is important to me to draw your attention to the interaction between

participants during keysigning. I observed a few parties in Germany and

found that the bulk of communication is about basic differences between

the participants.

Here, I would like to discuss to which extent the ritual is influenced

by categories like nationality and what this means for a community that

wants to be international.

German as lingua franca at international events in Germany

During the first part of a keysigning party, the attendance list is checked:

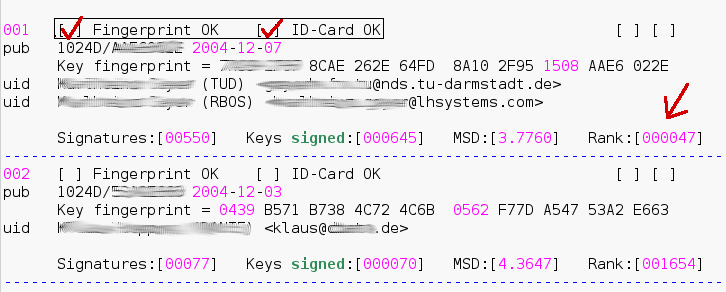

Figure 4: On the attendance list of a party there are checkboxes to

note whose key finger print and ID card has been checked.

Are all those present who applied for the event? Do they all confirm

that the finger prints of their keys are authentically reproduced on the

list?

At international key signing parties I observed several times that

during the welcome or the check of attendance single persons piped up

and said they did not understand German. They asked if it was possible

to continue in English or to translate. Language is linked to

provenance. By defining German as the lingua franca on international

community meetings in Germany, some people unintentionally make an issue

out of their different background by asking for translation. Generally,

it's no problem for anyone to switch to English, but evidently nobody

came to think of it before. This behaviour produces a rule in common

practive: participants speak German.

Passports: the artefact in the centre of attention

Figure 5: Control of passports during a key signing party.

(Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/arctanx/2395905554/

by arctanx under a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en)

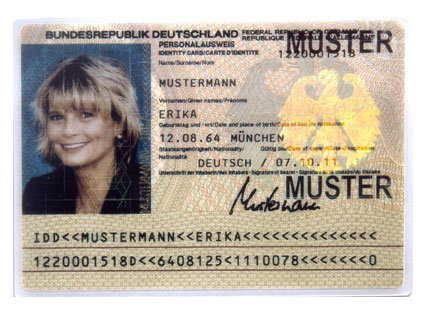

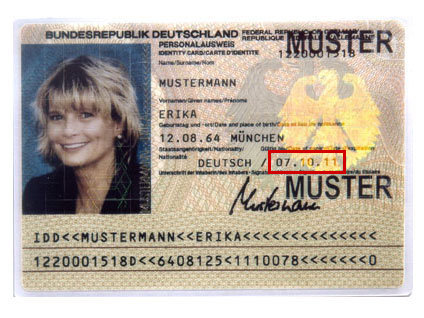

The only certificate that proofs one's identity is issued by state

departments: In Germany this can be a passport or an identity card.

Remarkably no driving licences are accepted.

At key signing parties the passport becomes the center of attention.

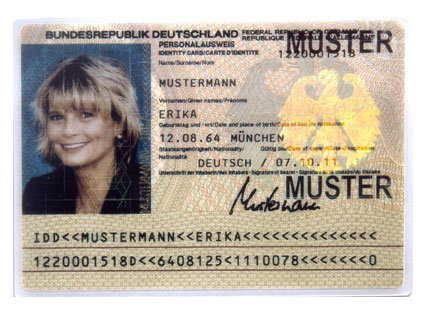

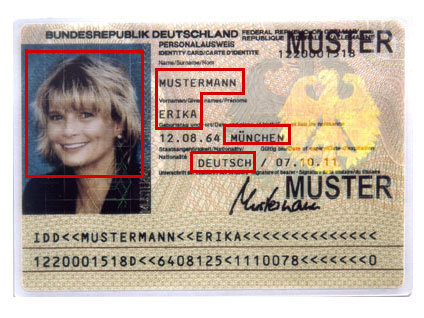

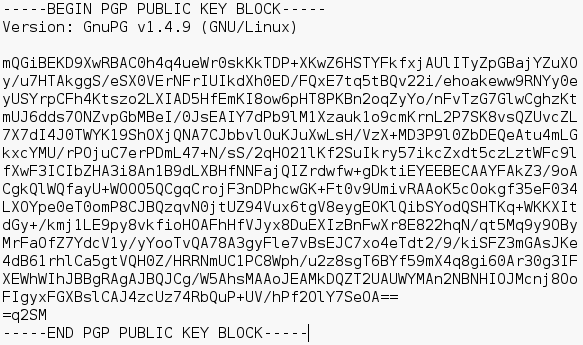

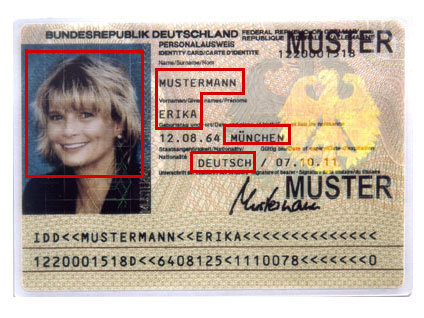

Figure 6: On the attendance list of a party there are checkboxes to

note whose key finger print and ID card has been checked.

(Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MustermannPA.jpg. This

image is in the public domain.)

A passport contains information that is picked up by the

participants to start brief, small talk-like conversations. Passports

thus offer the possibility to talk about where people come from, about

their appearance (photo), age, and gender.

Figure 7: Topics for small talk.

This might explain why talking about otherness becomes such an integral part

of key signing.

Let me go into detail:

Dialect as deviance

On the one hand foreign languages were an

issue at the key signing parties but I also observed that dialects or

languages as Swiss German constantly were a topic of conversation. “Say

a sentence in Swiss German or Swabian to prove where you come

from.” Remarks like this are meant to be jokes. My point is to say

that also by jokes the construction of otherness (or worse, of inequality) is

perpetuated.

Names as carriers of exoticism

I frequently observed that special attention is paid to participants'

names. Questions like ''Where does that name come from?'', ''How do you

pronouce that?'' are very common. The

same people were asked again and again during a key signing party. Their

interaction partners

tried to pronounce their names and made comments like "oh, cool".

Surely this is meant to be friendly. One wants to demonstrate to be interested in the partner. But I

argue that this has an effect: It gives an exotic distinction to people

who bear uncommon names. There is no personal exchange with anyone during a

signing party.

The interaction is restricted to noticing exotic names and maybe

finding them "cool". At the same time, making someone appear exotic,

confirms a norm: the non-exotic, commonly known names correspond to the norm.

(This makes me think of situations in which people wearing a veil are

told that their German is good...)

Authenticity and validity of passports

What is recognized as an identification paper? In Germany official

identification papers are passports and ID cards. Elsewhere, this is

different. Not only did I observe that participants utter doubts in the

authenticity of non-German identification papers, often enounced as jokes (e.g.

"self-made in colour printer"). But also I saw that in some

cases, people refused to sign a key of someone who brought, for example, a

Swiss driving

licence which for him or her is a valid identification paper.

Individuals can decide to produce others as untrustworthy persons

or not.

One could here talk of a lack of cross-cultural competence. The norm is

given by the majority of the attendants. It seems difficult to put

oneself in the position of someone who knows different norms and to

accept the papers they bring as equivalents of the own.

What often happens is that participants have expired passports which

confronts the crowd with a problem: Shall they obey to the strict rules of key

signing and refuse their trust or shall they turn a blind eye to the

rules? In my opinion, such moments of irritation show paradoxes in the

ritual. They raise the question what is a "trustworthy" communication

partner? An honest and law-abiding citizen who at once exchanges expired

papers?

Gender

We have heard a lot about the community being male-dominated.

Not surprisingly, there are very few women present at key signing parties as

in most parts of the community.

At this ritual, I had the general impression that where people come from

is made much more important than their gender. But I observed situations

in which gender is subtly meaningful:

One example was during the check of attendance: Everyone is taking notes

on one's list, to fill in who is attending the event. The heads are

turned down towards the lists while the names are called. The moment

a female name is called, all the heads turn up to look at her.

A second example were comments during the check of identity. Someone

calls out loudly "Ah, you always stick longer to talk to women!"

Knowledge is a prerequisite

At big key signing parties, all

knowledge about key signing is required. No explanations are provided

in the course of it. There ist no room for questions. The attendants do

not challenge the abstract idea of building up a "web of trust", let

alone ask how e-mail encryption or key generation work.

At the big events, so-called newbies stood in the way. They did not

understand which principle the crowd followed lining up in a queue.

The one small party I saw, with about 20 participants, was an exception.

Here, the organizers provided quite a lot of information on how the

ritual is carried out. They even reserved a whole hour before the actual

meeting for answering questions. However, I did not see many

persons who asked for an introduction.

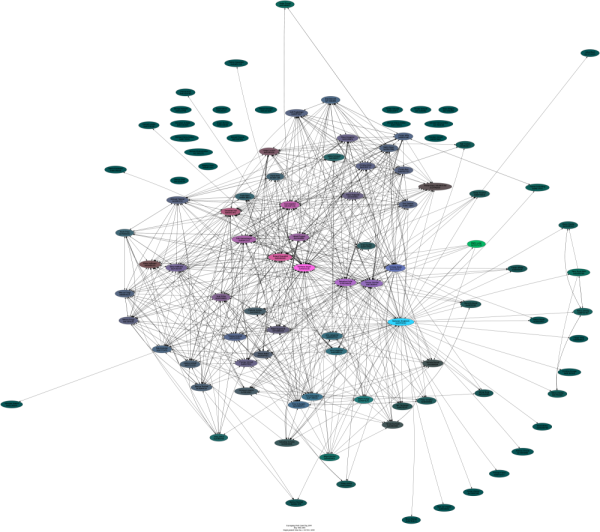

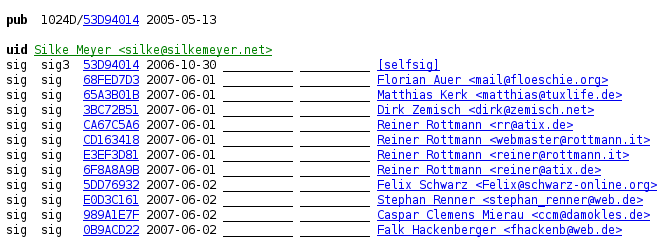

Figure 8: Here, the participants' place on the ranking list of the best

interlinked keys are mentioned on the attendance list.

Key signing thus mainly is a ritual for experts.

There is even a ranking

list of experts on the internet: the one thousand keys that are best

interlinked with other keys. During the parties some participants kept

joking about their high positions in concurrence to others', while beginners

did not know what they were on about.

Summary: Key signing as a practice of othering

I see a fundamental paradox in the ritual of key signing:

One the one hand, the community criticizes the establishment of a

surveillance society. Amongst others, encrypted communication is

important to them to protect their privacy from the authorities. One

might say that key signing is a public demonstration of people who want

to stress their consciousness of data being "sensitive". This raises the

question why the "web of trust" is published online so that whole social

networks are easy to reconstruct by the signatures.

On the other hand, the state is

handing out the only accepted proof of identity, namely passports.

I assume that the relevance of papers in the ritual is one reason for

nationality, language and provenance being made important apart from the

fact that we all probably have these categories quite well incorporated.

What other ways we can think of to build up trust...?

We have seen that the discursive production of otherness is a

constitutive part of key signing.

I would say that two sorts of "others" are produced in the

ritual:

Figure 9: No trust without valid identification papers

First, there are persons who are not trustworthy because they do

not have valid or accepted papers, but who take part in the party. Their

disobedience to the rules of key signing makes them suspicious. In this

logic, only citizens are trustworthy. The identification with one or

more nationalities are crucial to be taken as an equivalent partner.

Figure 10: Otherness is mentioned over and over again.

Second, there are "others" whom can be trusted by signing their

keys (because they do have valid papers),

but whose "otherness" has to be mentioned over and over again. They

deviate from the average

participant because of their background or body, those who have uncommon

names, or speak in a different way. Every mentioning updates the

inscription as "other" and helps establishing the norm.

Thereby, nationality becomes one fundamental category that structures

the practice of key signing.

Quite a few of my observations allow conclusions as to a lack of

cross-cultural competence.

It remains to consider the question what the norm actually is. The huge

majority incorporating the norm of key signing attendants was in these

cases of German nationality, German speaking, and of German offspring,

male and specialists in key signing rather than newbies.

Of course, my image is not that homogenous. I have to mention other

topics of small talk like the community projects the participants are

active in. The list of attendants can give clues as to these projects

(e-mail addresses). Jokes about new ID cards containing biometric data

are quite common, too. This can be understood as political criticism in

a context where people nevertheless rely on those ID cards as

identification papers. And I have to mention little conversations

alongside the events where questions concerning the ritual were

answered "inofficially".

What's the point of my talk?

Such processes of othering I described have effects on the community.

Drawing on basic distinctions between people makes it easy to open up

classifications based upon characteristics. My observations make me pay

special attention because the same processes basically underly

discrimination.

In this context, it is very hard to distinguish between friendly jokes

towards the guests of the event and the subtle drawing on discriminating

patterns that are deeply embedded in mainstream society.

Such cognitive patterns are long-lasting, often structured in a

dichotomous way and they are often evoked unconsciously. They are based

upon the premise that people and societies

differ from each other in significant ways. This can be the base for

racism, sexism, classism, homophobia and all sorts of discrimination.

The outstanding issues are

- Which social power relations are reproduced in practices

of the FLOSS community?

- How is this related to the community's claims to work

in a different way?

- What can be done to raise people's awareness of

potentially discriminating behaviour especially when

they just wanted to be friendly or funny without

accusing them of discrimination?